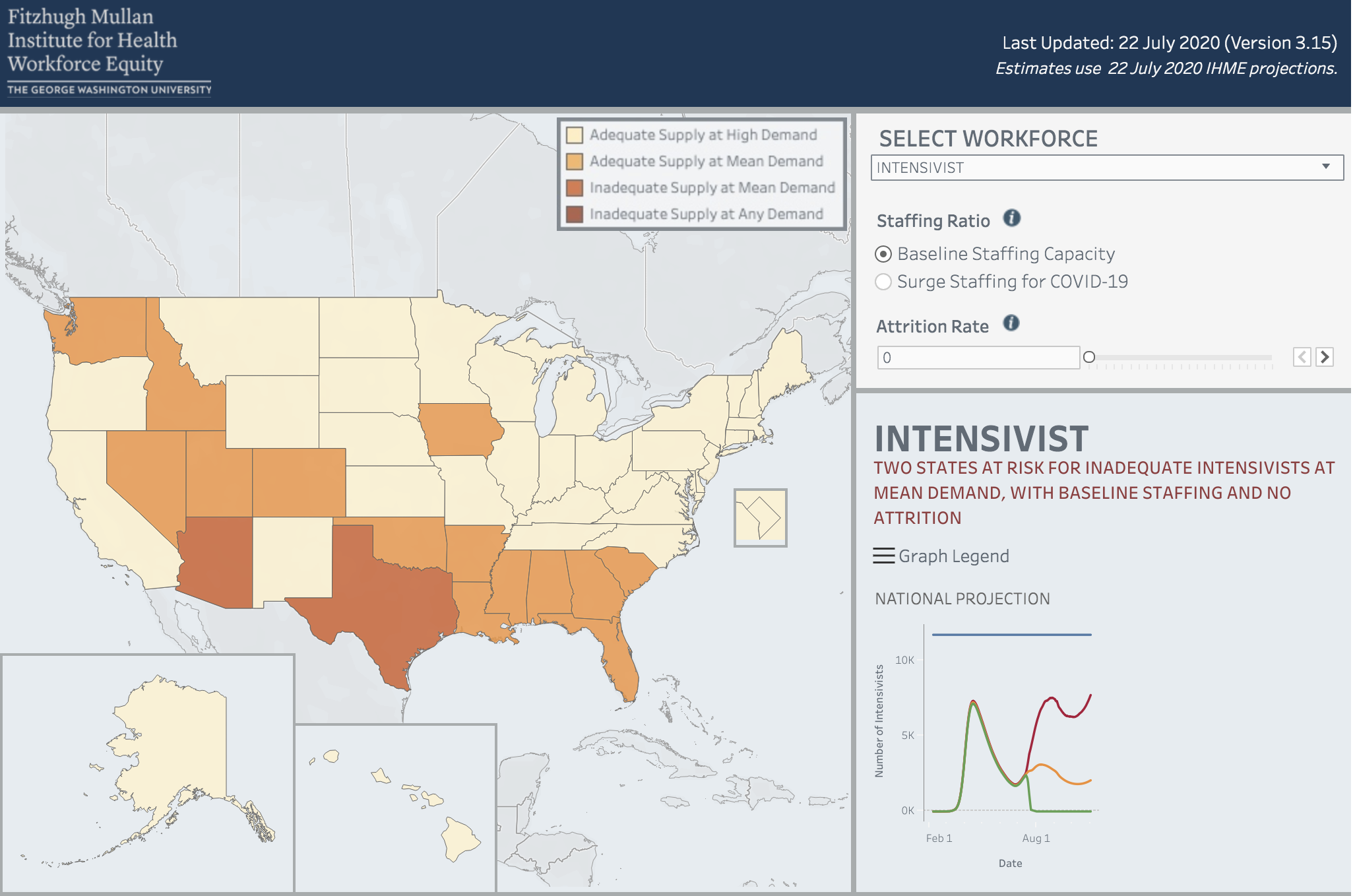

WASHINGTON, D.C. (July 27, 2020) — A hospital workforce estimator developed by the Fitzhugh Mullan Institute for Health Workforce Equity (Mullan Institute) at the George Washington University Milken Institute School of Public Health (Milken Institute SPH) finds 11 states with surging COVID-19 rates are currently at risk of straining their supply of intensivists, doctors who are trained to work in intensive care units (ICU). Two states are already facing shortages in these highly trained doctors, according to a weekly update by the Mullan Institute.

“This week’s update shows that Alabama, Arkansas, Florida, Idaho, Louisiana, Mississippi, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah and Washington all could face a shortage of intensivists. In these states, less than 50 percent of intensivists are available for non-COVID patients,” said Patricia (Polly) Pittman, PhD, director of the Mullan Institute. “Arizona and Texas face a shortfall of intensivists even just for the COVID-19 patients. Our estimator suggests that a rapid increase in severely ill COVID-19 patients could overwhelm understaffed ICUs in many states.”

While the media has largely focused on the danger of depleting ICU beds, workforce shortages to staff these units can be an even greater problem. New beds can be set up in other hospital units, or even outside the hospital setting, but ICU staffing is relatively finite. The Mullan Institute estimator allows states to anticipate shortages and provides resources on emergency measures that can be used to quickly to add ICU staff.

The timing of the shortfalls varies by state. Six are not expected to have hospitalizations peak until early November, suggesting that these are the states that are most at risk of shortages and in need of workforce planning. These states are Idaho, Nevada, Oklahoma, South Carolina, Utah and Washington.

The purpose of the State Hospital Workforce Deficit Estimator is to help states and the federal government gauge the demand for health care professionals under different scenarios of COVID 19 infection rates and attrition. Attrition refers to the loss of health care workers due to illness, childcare or other reasons, such as burnout. The estimator allows state and federal policymakers to plan for looming spikes in COVID-19 cases and prepare by developing surge staffing plans, implementing emergency licensing for inactive health personnel, and/or recruiting from other states and the federal health workforce, among other measures.

To assess the demand for health care workers needed to care for projected COVID-19 and non COVID 19 patients in hospitals, Pittman and her team used data from the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation’s (IHME) model of demand for hospitalizations. For workforce supply data, they used the National Providers Plan and Provider Identification System; Medicare claims data; American Hospital Association data and the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses.

“We believe these are likely conservative estimates of the potential shortfall, as they are based on mean IHME updates, not the highest estimates, and do not account for attrition of providers due to workforce infections and quarantines,” Pittman said.

The State Hospital Workforce Deficit Estimator has an interactive map that shows state-by-state shortfalls in health workers needed to meet the COVID-19 and non COVID demand. The interactive toll allows users to change some of the assumptions in their states to gauge the adequacy of the state’s workforce to care for ICU patients.

A report based on the available data as of late July can be accessed here.