Survey of villagers and health care workers will identify cultural practices, beliefs and other factors that might be addressed in order to halt the spread of the virus

Media Contact: Kathleen Fackelmann, [email protected], 202-994-8354

WASHINGTON, DC (May 12, 2015)—The Department of Global Health in Milken Institute School of Public Health (Milken Institute SPH) at the George Washington University has received a $100,000 grant from the National Science Foundation (NSF) to study the ethnic, cultural and spiritual beliefs about Ebola virus disease among villagers and health care workers in the West African country of Guinea. Such beliefs and practices can affect the comprehension of public health messages and the ability of healthcare personnel to deploy interventions to reduce transmission of the deadly virus, according to Milken Institute SPH researchers.

“Infection spread throughout much of Guinea and into neighboring countries,” said Sally Lahm, PhD, a professorial lecturer and research scientist in global health at Milken Institute SPH and one of the lead investigators on the study. “With this study, we hope to identify cultural traditions and other factors that might affect the public health effort to get to zero new cases in the affected West African countries.”

The World Health Organization recently reported that the number of lab-confirmed cases of Ebola in Guinea has been increasing, and is now declining slowly as healthcare teams increase their efforts. As of May 3, 2015, the World Health Organization (WHO) reported a total of 18 confirmed new cases in West Africa and nine were in Guinea. All nine new cases in Guinea were reported from a prefecture in western Guinea called Forecariah, which borders a region in Sierra Leone that also has new cases of Ebola. Experts worry that the spread of Ebola in this trans-border area could seed a future explosion in new cases in both countries—if it is not stopped.

In fact, Lahm, along with Amira Roess, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor of global health at Milken Institute SPH, who is co-principal investigator of the study, applied for and won an NSF grant through the Rapid Grants Program funding mechanism, which awards grants for proposals on subjects which require rapid data collection and dissemination of results, such as urgent public health threats.

The four-month study will include a two-month field survey in which Lahm will travel to numerous villages throughout Guinea to engage community elders, traditional leaders, residents, and rural health care workers in interviews and group discussions to identify beliefs and cultural practices surrounding Ebola. Few studies of such underlying beliefs and comprehension of public health messaging have been done to date despite the fact that such knowledge is often key to putting in place a successful emergency response, Lahm and Roess said. The team drew upon their previous work in Ebola-affected countries in Central Africa where they were involved in health education, social mobilization campaigns, and research on the natural history of Ebola virus, to design this study.

The current Ebola epidemic started in a remote, heavily forested area of southeastern Guinea and eventually spread to nearby Sierra Leone and Liberia. It is the largest Ebola virus outbreak in history and poses a threat not just to the West African region but to other countries as well.

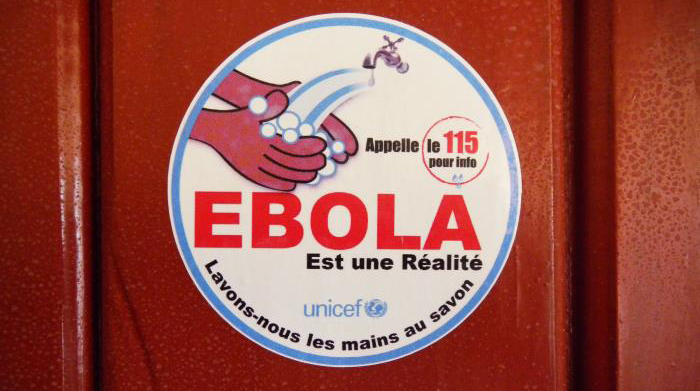

A defining feature of the epidemic has been the resistance of affected communities to prevention measures that public health workers have tried to put in place. For example, Roess says many local people with symptoms of Ebola have refused to go to treatment centers or relinquish the bodies of dead relatives. Such resistance can lead to continued spread of the disease, especially when local residents don’t understand how the virus can be passed from one person to the next, she said.

With the survey, Lahm and her research team —subject matter experts from Guinea—will try to find out what local residents know about Ebola and how it is caused. By documenting what villagers actually know, the researchers can begin to pinpoint areas of misinformation or mistrust. For example, if residents refuse to go to treatment centers because they believe they will not be helped and will simply die there, outbreak response teams can address that fear and design more culturally appropriate public health messages and education campaigns, Lahm says.

In addition, Lahm and her research team will also interview rural health care workers in these areas to find out how they view Ebola and if they received and understood Ebola-related training and materials. Do they understand it is a virus and spread by close contact and not by malevolent spirits—a belief that is widespread among patients, for example.

Roess and Lahm will also use the results of the survey as well as Global Positioning System (GPS) data to create maps of Guinea that have not only information about the number of new cases but also the beliefs/traditions in the regions that might contribute to the spread of the virus. Public health researchers could use such maps to track the epidemic and identify areas as well as strategies that might work to ease fears, counter myths—and stop Ebola at the same time, Roess says.

About Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University:

Established in July 1997 as the School of Public Health and Health Services, Milken Institute School of Public Health is the only school of public health in the nation’s capital. Today, more than 1,700 students from almost every U.S. state and 39 countries pursue undergraduate, graduate and doctoral-level degrees in public health. The school also offers an online Master of Public Health, MPH@GW, and an online Executive Master of Health Administration, MHA@GW, which allow students to pursue their degree from anywhere in the world.