The link between prenatal exposure to particulate air pollution and reduced birth weight and increased rates of lower respiratory tract infections and asthma in children is something scientists have known about for awhile, but why this happens is not well understood. Natalie Johnson, PhD, an assistant professor of Environmental and Occupational Health at the Texas A&M School of Public Health, is one of the researchers who is trying to shed light onto this important issue. She recently came to the Department of Environmental and Occupational Health (EOH) at GW’s Milken Institute School of Public Health to talk about her research.

The department brings in one or two experts each month to discuss their research, and these popular seminars are one of the ways our students learn about current EOH topics.

The World Health Organization estimates that 1.7 million infants die annually due to exposure to ambient air pollution, Johnson reminded attendees. Her research interests encompass how exposure during both pregnancy and early life can cause respiratory dysfunction later in life.

Some of Johnson’s data come from a maternal exposure study she conducted in the Lower Rio Grande Valley in southern Texas near the Mexican border. “Asthma is one of the major public health issues in these communities,” she explained. The area’s population is growing rapidly and children’s rates of hospitalizations for asthma are elevated, she explained. She worked with local clinics to recruit 17 healthy women who were in their third trimester of pregnancy.

Personal air monitors

Potential drivers for the high asthma rates in the area include traffic pollution related to emissions from vehicles that are idling as their drivers wait in lines to cross the border between the U.S. and Mexico. The women in the cohort were equipped with backpacks that contained personal air monitors which collected data on air pollutants including particulate matter and polyaromatic hydrocarbons, which the expectant mothers used for a day in advance of three prenatal appointments.

The data collected in the study showed that the women’s proximity to a major highway raised the level of pollutants to which they were exposed, but the highest exposures occurred at home due to cooking. Cooking can be an important source of exposure to particulates, Johnson points out.

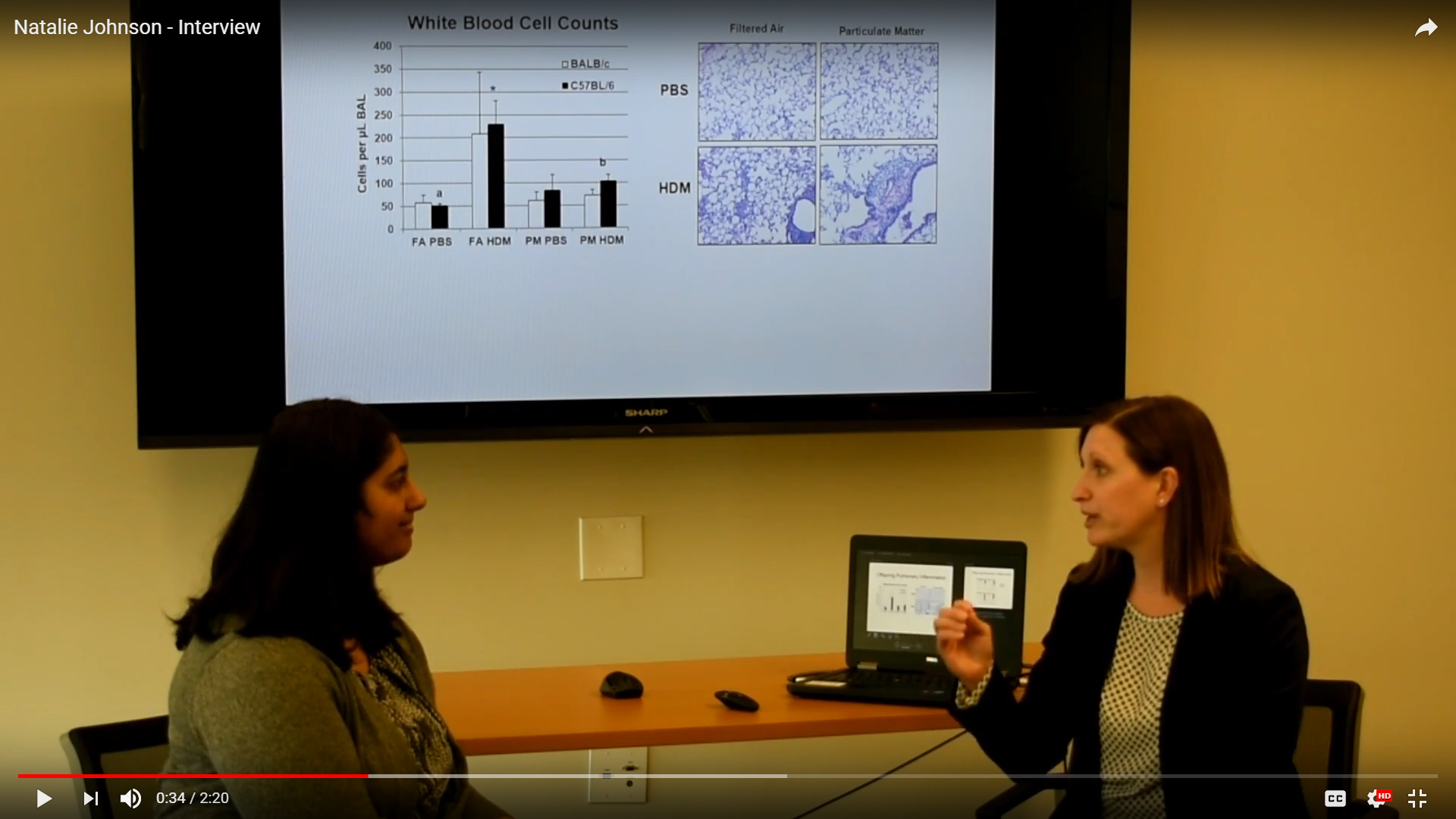

Because she is trained as a toxicologist, Johnson is also working with mouse models to investigate the mechanisms underlying respiratory effects resulting from in-utero exposure to particulates and other pollutants. She and her colleagues used chambers to expose two strains of mice to air with levels of diesel exhaust and other pollutants that are characteristically found in the air around Houston, Tex.

After the mouse dams delivered their offspring, some of the pups were exposed to house dust mites, which can be an asthma trigger in the mouse model (as well as being a human allergen). The levels of immune cells in the lungs of mouse offspring that were exposed to the polluted air were elevated, but the researchers found evidence of immune suppression in the mice that were exposed to the dust mites.

Johnson recently received an R01 grant from the National Institutes of Health to further investigate the mechanisms underlying how exposure to particulate matter impacts infant respiratory disease. Her research is also looking at how such exposure could impact the developing immune system. The model will include investigations into the impacts of maternal stress and whether dietary interventions may provide a protective effect.

After the seminar, Anita Desikan, a student in the EOH Environmental Health Science and Policy MPH program, asked Johnson more about what she currently suspects are the mechanisms underlying how prenatal exposure to air pollution may be altering immune cell differentiation in the lung. Desikan is a Fulbright Scholar with a MS in biomedical science who has authored or co-authored seven scientific publications, including original research finding an association between air pollution and stroke mortality in the city of London. In response to Desikan’s question, Johnson talked about how the exposures that she is studying could lead to the development of asthma or an enhanced susceptibility to infections.

View the interview, which includes Johnson’s thoughts on the potential for windows in early infancy where it may be possible to intervene, here

View Johnson’s seminar here