WASHINGTON, DC (October 17, 2017)— A new analysis of the evolutionary history of HIV in the District of Columbia gives researchers a more comprehensive picture of the epidemic over time. A team led by researchers at the Milken Institute School of Public Health (Milken Institute SPH) at the George Washington University (GW) conducted the analysis and found clues about HIV that might be used to provide better care and even prevent new cases of HIV in the near future.

“The study helps give us a better idea about the genetic diversity and subtypes of HIV in the District,” says lead author Marcos Pérez-Losada, an assistant professor in the Computational Biology Institute (CBI), which is based at Milken Institute SPH. “Additional research must be done to find out more about the resistant mutations of HIV and other findings that could help prevent new cases of HIV.”

Researchers know that DC has one of the highest rates of HIV infection in the country, with a prevalence rate of about 2 percent. Yet few HIV sequences from the nation’s capital are available in databases to assess the evolutionary history of HIV to help identify factors that contribute to the HIV epidemic.

To plug that gap, Pérez-Losada and his colleagues at CBI teamed up with other GW colleagues from the DC Cohort research team as well as the District of Columbia Department of Health, and Laboratory Corporation of America to analyze the HIV sequences and clinical and behavioral data collected from the DC Cohort. This analysis used anonymized data from a subset of HIV-positive DC Cohort participants, who were receiving care at 13 clinics in the District from 2011 to 2015.

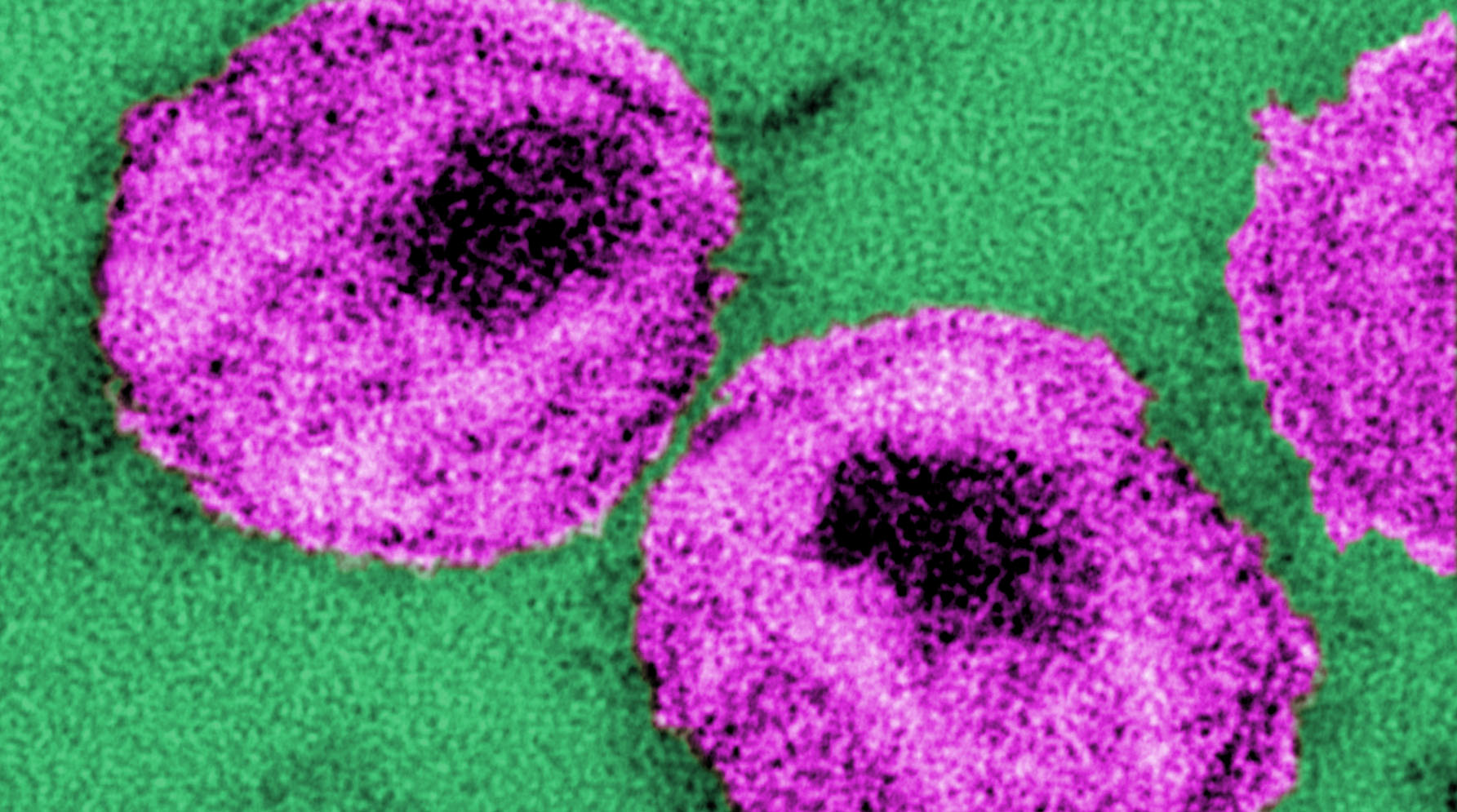

Like other fast-evolving viruses, HIV has the ability to change over short periods of time (few years). Using DNA sequences of the virus, the team found that more than 90 percent of the available HIV sequences collected from DC Cohort participants were subtype B. That finding suggests that the DC HIV epidemic is consistent with the United States epidemic where subtype B is also the most common type of HIV, the authors say.

The team also detected a high prevalence of drug resistant mutations in the HIV samples tested, a finding that has potential treatment implications. By coupling these data with other data on HIV drug resistance in DC, researchers might be able to use this knowledge to help guide doctors toward drugs that are more likely to be effective against HIV, the authors say.

Finally, Pérez-Losada and his colleagues found that some subtype B infections fell into clusters, suggesting that transmission chains play a role in the spread of HIV in the District. Learning more about such clusters can help inform the work of health department colleagues to potentially prevent new cases of HIV from occurring. And they can also identify correlates of transmission such as risk factor or geography and use those for more targeted intervention and prevention approaches.

The article, “Characterization of HIV diversity, phylodynamics and drug resistance in Washington, DC,” was published online in the scientific journal PLOS One. The study was supported by funding from the National Institutes of Health, a DC CFAR HIV Phylodynamics Supplement award, and a supplement from the Women’s Interagency Study for HIV.