Study suggests that bacteria of the human nose are not genetically predetermined and that some nasal bacteria may protect against MRSA

Media Contact: Kathleen Fackelmann, [email protected], 202-994-8354

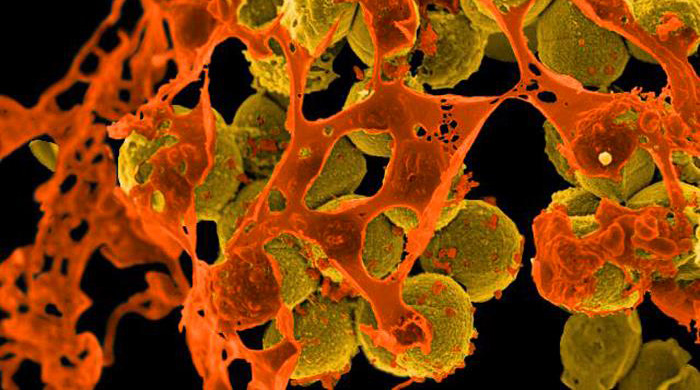

WASHINGTON, DC (June 5, 2015) — Staphylococcus aureus — better known as Staph — is a common inhabitant of the human nose, and people who carry it are at increased risk for dangerous Staph infections. However, it may be possible to exclude these unwelcome guests using other more benign bacteria, according to a new study led by scientists representing the Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen), the Statens Serum Institut, and Milken Institute School of Public Health (SPH) at the George Washington University.

The study, published today in the AAAS journal Science Advances, suggests that a person’s environment is more important than their genes in determining the bacteria that inhabit their noses. The study also suggests that some common nasal bacteria may prevent Staph colonization.

“This study is important because it suggests that the bacteria in the nose are not defined by our genes and that we may be able to introduce good bacteria to knock out bad bugs like Staph,” said Lance B. Price, PhD, the director of TGen’s Center for Microbiomics and Human Health and a professor of environmental and occupational health at the Milken Institute SPH. “Using probiotics to promote gut health has become common in our culture. Now we’re looking to use these same strategies to prevent the spread of superbugs.”

The multi-center research team looked at data taken from 46 identical twins and 43 fraternal twins in the Danish Twin Registry, one of the oldest registries of twins in the world. “We showed that there is no genetically inherent cause for specific bacteria in the nasal microbiome,” said senior author Dr. Paal Skytt Andersen. Dr. Andersen is head of the Laboratory for Microbial Pathogenesis and Host Susceptibility in the Department of Microbiology and Infection Control at the Statens Serum Institut and an adjunct professor at the University of Copenhagen.

The so-called nasal microbiome is the collection of microbes living deep within the nasal cavity. This research might ultimately lead to interventions that could route Staph from the nose and thus prevent dangerous infections, including those caused by antibiotic-resistant Staph, the authors say. Studies suggest drug-resistant Staph infections kill more than 18,000 people in the United States every year.

The researchers also looked for possible gender differences and found that contrary to past studies that showed that men are at higher risk for Staph nasal colonization — this study, using DNA sequencing, found that there is no difference between men and woman in the likelihood of nasal colonization by Staph.

“This was a surprising finding. I felt like I was one of the MythBusters guys. For years, most scientists agreed that men were more likely to be colonized by Staph than women. But now we see that that was probably just an artifact of using old methods and that men just tend to have more bacteria in their noses, which makes them easier to culture,” said Dr. Cindy Liu, a pathology resident at Johns Hopkins School of Medicine and the study’s lead author.

Importantly, the study found evidence that other types of organisms can disrupt Staph. A prime example is Corynebacterium, a mostly harmless bacterium that is commonly found on the skin. The study found that having high amounts of Corynebacterium in the nose was predictive of having low amounts of Staph and vice versa.

“We believe this study provides the early evidence that the introduction of probiotics could work to prevent or knock out Staph from the nose,” said Dr. Liu.

The next step will be to prove the findings of the study’s models in a laboratory setting.

Funding for this work, Staphylococcus aureus and the Ecology of the Nasal Microbiome, was provided by 1R15DE021194-01 and AI101371-02 from the National Institutes of Health. The Danish Twin Registry is supported by a grant from the National Program for Research Infrastructure 2007 from the Danish Agency for Science Technology and Innovation. The content of this publication are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not represent the official views of the funding agency.

About Milken Institute School of Public Health at the George Washington University:

Established in July 1997 as the School of Public Health and Health Services, Milken Institute School of Public Health is the only school of public health in the nation’s capital. Today, more than 1,700 students from almost every U.S. state and 39 countries pursue undergraduate, graduate and doctoral-level degrees in public health. The school also offers an online Master of Public Health, MPH@GW, and an online Executive Master of Health Administration, MHA@GW, which allow students to pursue their degree from anywhere in the world.

About TGen:

Translational Genomics Research Institute (TGen) is a Phoenix, Arizona-based non-profit organization dedicated to conducting groundbreaking research with life changing results. TGen is focused on helping patients with cancer, neurological disorders and diabetes, through cutting edge translational research (the process of rapidly moving research towards patient benefit). TGen physicians and scientists work to unravel the genetic components of both common and rare complex diseases in adults and children. Working with collaborators in the scientific and medical communities literally worldwide, TGen makes a substantial contribution to help our patients through efficiency and effectiveness of the translational process. For more information, visit: www.tgen.org.